The concept of Takt is central to Lean operations. Without a full understanding of the concept anything else fails to make sense.

With the concept of Takt we can plan and manage capacity, plan operations, balance manufacturing (or transactional) activity and calculate the labour requirements for a given workload.

Time is the single best measurement of competitiveness and just about everything can be measured in terms of time or resolved to it, time is to Lean as Defects are to Six Sigma.

The concept of Takt is pretty simple, the word “takt” translates form German as stroke, bar or beat. Many musicians use a metronome, a device that marks time at a selected rate by giving a regular tick, to help them keep time in a piece of music – if you have a German one you will probably find it is called a “Taktmesser”, literally a beat measurer.

Operating to takt means to produce at the pace of a constant drum beat – that beat determined by the customer demand. The drum beat can be any unit of time that you choose, as long as it is sensible, and can be seconds, minutes, hours, weeks and so on. It is the frequency at which one piece of work should be completed to match customer requirements, and as such it sets the pace of operations to match pace of customers requirements.

Takt time is not the same as cycle time, which is the normal time to complete an operation on a product (which we want to be less than or equal to takt time).

Takt time is calculated pretty easily,

Where available time means the elapsed clock time available and the customer demand is the actual or predicted demand over the time period being considered.

It is important to use for the available time the actual clock time – NOT the labour hours, some measure of efficiency, adjusted hours or any other artificial construct. Use ONLY the actual working hours.

Let’s have a look at a simple example assuming a 40 hour week and a customer demand of 40 units per week …

In this simple example the takt time will be clearly 1 hour. In other words 1 unit must be completed each and every hour in order to meet customer demand.

That’s a little bit too simple though. Your people may well attend for 40 hours but out of that you will probably allow them a number of non productive time elements, time when you know your aren’t going to be productive.

Let’s take this example …

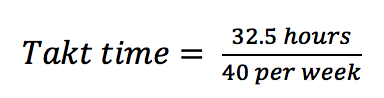

Our operations work from 9am to 5pm Monday to Friday. A total attended time of 40 hours, but they take a 30 minute lunch break per day and have a 15 minute break morning and afternoon each day. So the total actual productive time is actually 35 hours. We have a 15 minute morning team meeting and a 15 minute afternoon team meeting daily, further reducing the actual productive time to 32.5 hours.

Our Takt time now becomes;

So you should be able to see that our takt time is now 0.8125 hours (or 48.75 minutes).

A short while ago I published an article on the benefits of U shaped cells here. A number of comments on the article revolved around balance, you should be able to see now that if each operation in the process I described takes less than or exactly the same as the takt time then we will meet customer demand (except for one small wrinkle which I will describe shortly).

It is worth pointing out that the net available working time should exclude scheduled non-working time but should not exclude things like time for changeovers, breakdowns, rework and so on, if you do that then you will ignore these losses in your productive time.

What you should do is to measure your Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) as described in my article here. Then use this to calculate your target cycle time …

So if your takt time is 48.75 minutes and your OEE is 85% then your Target Cycle Time (TCT) is Takt Time X OEE or in this case 41.43 minutes. You can see quite clearly what the real cost to your productivity is, you could even calculate it in terms of percentage loss or products lost.

Having established out Takt time we can now calculate the labour required to complete all the tasks.

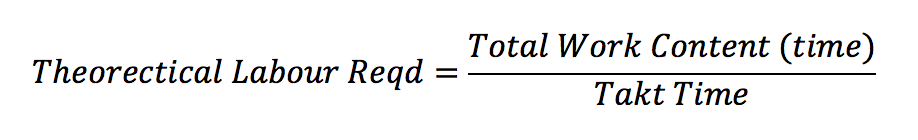

The theoretical minimum labour required is given by …

Here the important distinction is “total work content” not cycle time. Here we want to use only the actual time the workforce actually has to be involved to accomplish the task. Loading or unloading machines for example is work content while standing staring at the machine while it completes the job is not.

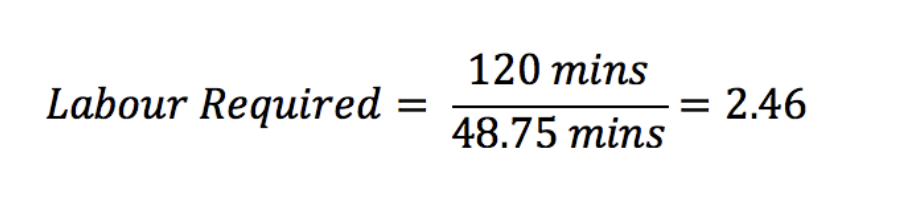

Let’s assume for this example that the total work content is 120 mins, we know the takt time is 48.75 mins so that gives is a labour requirement of;

So we need 2.46 operators to complete all the tasks – we can’t easily have less than a full person and of course we are unlikely to operate at 100% efficiency so this means we need 3 operators. The next steps of course are to figure out how we can reduce the work content or inefficiencies in the process to get us to 2 operators.

Now let us turn our attention to the allocation of labour tasks to a defined level to maximise labour utilization, known as balancing.

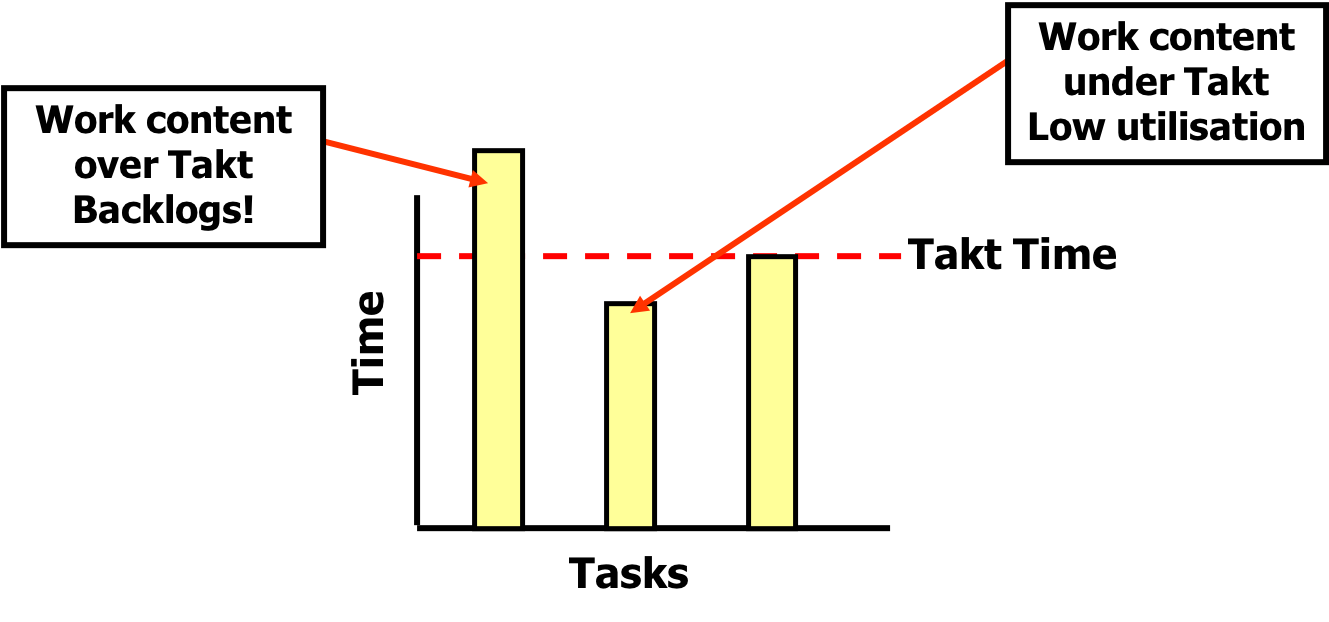

The diagram below shows three tasks, one of them is above takt time which will result in an inability to meet customer requirement, one is at takt and one below takt which results in low utilisation of equipment and people.

Our objective is to build work content that is as close to Takt as possible while not exceeding it. Using Target Cycle Time here adds a further dimension and is to be encouraged.

Takt time, and hence everything that feeds off it, will change as demand or available time varies. You should calculate Takt frequently – the best manufacturing orgainsations calculate it several times daily. Our challenge is to manage Takt – we can’t set it.

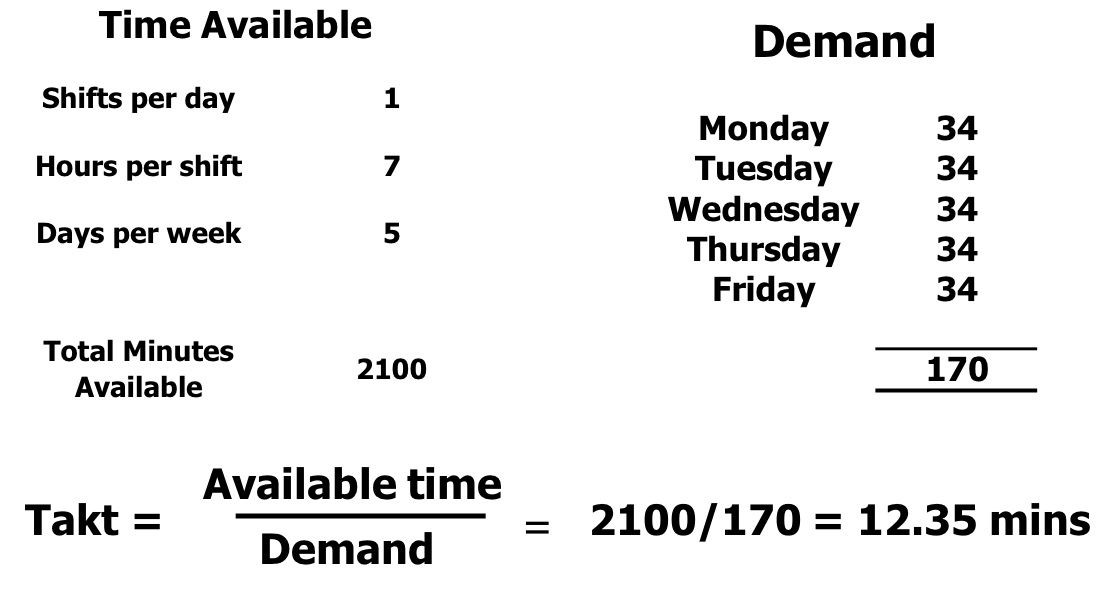

Let’s have a look at a worked example.

In order to meet customer demand we need to complete a work cycle every 12.35 minutes.

Let’s say that the above example relates to production of some widget, we have measured the total work time required to complete a single cycle of work at 18 minutes.

Demand averages 34 per day and hence we can calculate the total labour required for the above example irrespective of the actual available.

So, daily labour time required = 18 mins x 34 units = 612 mins (10.2 hours) and labour required is then = Total Work Content/Takt Time = 18 mins/12.35 mins = 1.46 people.

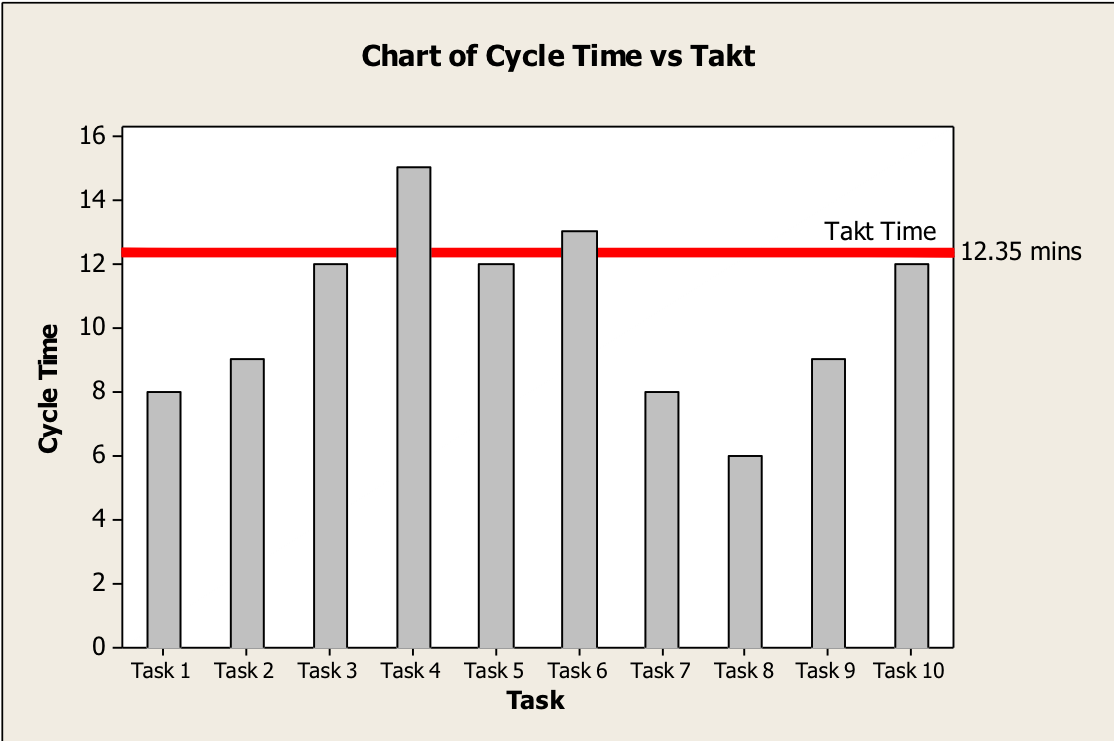

The following is an example of a process with multiple tasks, where would you focus your efforts to improve output?

If you said tasks 4 and 6 then you would be right. Our objective here should be to reduce the time required for tasks 4 and 6 to bring them into takt (or target cycle time where you use that). When you have examined these tasks, and if there is no opportunity to remove time, then you should try and move work content from the tasks over takt into other tasks that are under takt.

But look also at task 8, that one is well below takt and therefore there is a waste of resources here. Could this task have its operations redistributed across the other tasks and free up equipment, personnel and so on?

Sounds pretty simple so far.

The previous examples have focused specifically on single processes but we can, and do, measure takt at a business level or a detail process level.

We need to be aware of demand variation and use kanbans as buffers or demand levelling to ensure consistency – this not easy in a transactional environment.

Consider also where different areas may operate different working patterns and the impact of flexible working time. Different areas can also have widely different OEE rates and these differences will impact on the Takt time of each area.

Every process has a Takt time … The objective is always to balance the process to Takt!

To ensure good flow Takt times must be balanced – out of balance work areas are a major source of problem.

Takt and load charts identify un-balanced operations and emphasis on these processes focuses resources to eliminate bottlenecks and improve flow.

Improved flow leads to improved performance and improved performance enhances customer satisfaction.

Where your process (be that step or total) operates above Takt then you should analyse the constraint processes by carrying out process observations and timings , analyse the work methods and remove non value adding work, improve material flows and implement improvement actions.

In summary;

Takt time is a tool that establishes the heart beat of the business, it is a measure against which operations can be balanced and can be measured at various levels in the organisation and there are a number of factors that need to be taken into account when calculating Takt.

Improving adherence to takt is a key element of throughput time reduction which in tunr is a key component of lead time reduction. Throughput time reduction focuses upon eliminating wastes within any system (notably waiting and transportation).

There is a clear relationship between inventory, output rate and throughput rate (Little’s Law) and this will be the topic of a forthcoming article.

About the author

Michael D Akers is a Partner with Advanced Analytics Solutions LLP. He is a Lean practitioner of over 35 years standing and the author of “Exploring, Analysing and Interpreting Data with Minitab”, he is a Lean Six Sigma Master Black Belt with over 30 years of practical application of problem solving in a range of industries including several years statistically analysing failures in an automotive OEM, he writes on improvement and strategy topics, consults around the world and his latest book is available on Amazon, Apple’s iBooks platform and Google Play.